A Grain of Maize: Markets and Agriculture in South Africa’s Land Reform Program

After apartheid, the democratically elected South African government promised to redistribute 30% of all white-owned agricultural land to Black South Africans (and to other South Africans of colour) by 1999 using a program that compensated existing landholders who voluntarily sold their land. But by 2016, the country had still failed to break the 12% threshold. My book project builds on my dissertation to understand why this project of racial restorative justice has fallen so short.

I argue that contemporary land reform has changed in a way that demands a new set of explanations. While land reform in the 19th and early 20th centuries was characterized by forceful expropriation, most land reform today is voluntary and compensated for the existing landholders. This change means that contemporary land redistribution is motivated by a new set of determinants that are rooted in market institutions. I argue that these new motivators of land transfers are related to the institutions surrounding existing landholders. First, landholders in certain commodity sectors maintain a regulated relationship with the state, which gives the state leverage over the sector and the ability to compel landholders to sell their land. Second, landholders in some sectors are organized and centralized, which allows them to respond to incentives to redistribute in a more cohesive manner.

To show the relevance of these institutions in determining what land is transferred and where, I rely on original semi-structured interviews and spatial data from two of South Africa’s provinces.

Empirical Chapters

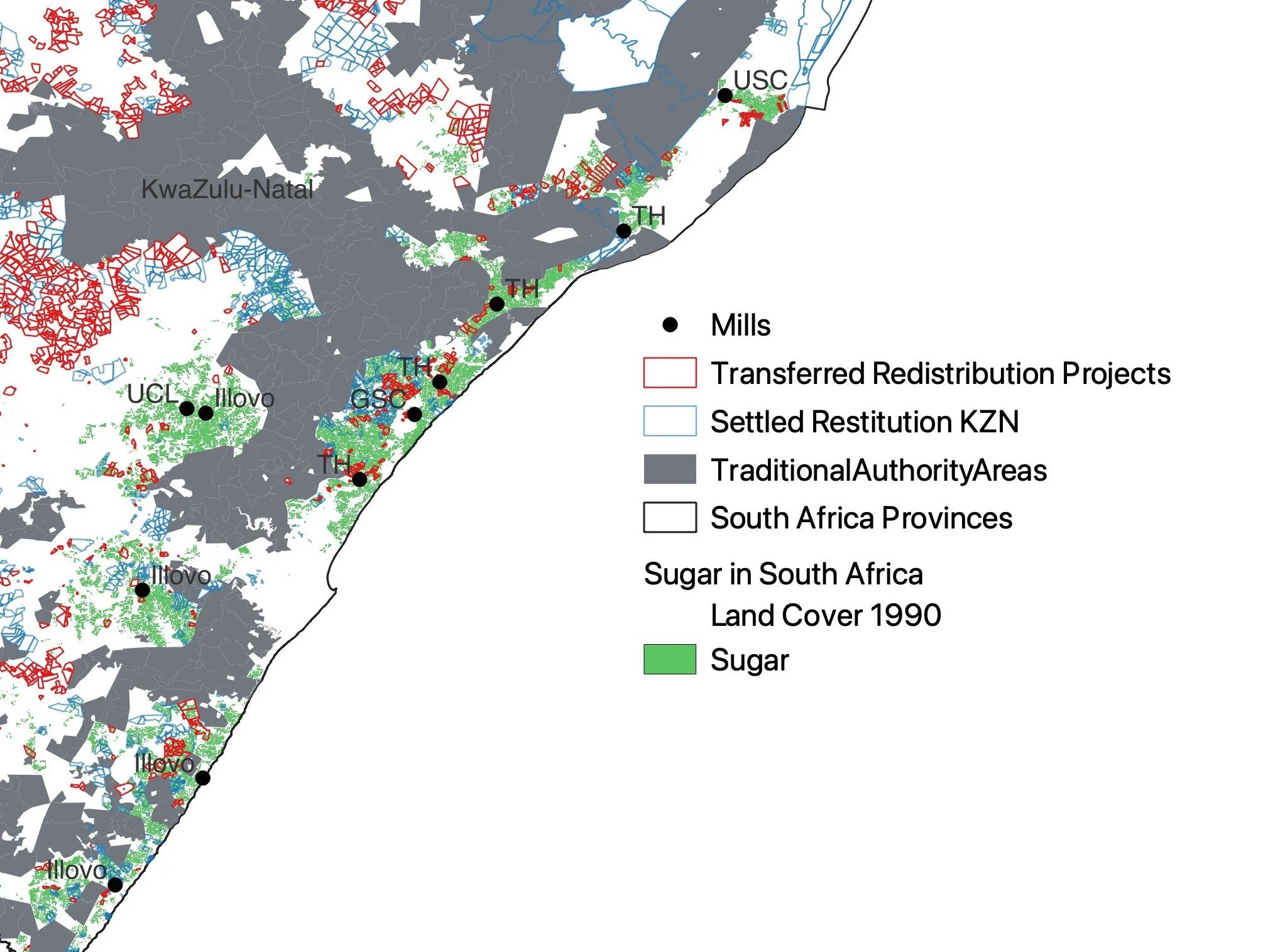

Sweetening the Deal: Regulation and Redistribution in South Africa's Sugar Sector

This chapter employs process tracing to analyze the case of South Africa’s sugar sector, where the sector has transferred over 20% of its land. I argue that these transfers cannot be explained by theories of clientelism, traditional authorities or patronage. Instead, the sector’s political economy drove early land transfers. Actors within the sector depended on regulatory frameworks (especially the sugar tariff) and thus had an interest in complying with the government’s land reform priorities. Further, the sector’s centralization around sugar mills allowed actors to act quickly and comprehensively on that incentive to transfer land.

When Life Gives you Lemons: Barriers to Redistribution in South Africa's Fruit Sectors

In contrast, the state struggled to redistribute land within the fruit sector, where high land prices and technically demanding agriculture made land transfers more difficult. Yet even in this unlikely case for land reform, the characteristics of the sector defined how landholders interacted with the state. As a deregulated sector, the state had little means to compel actors to transfer their land. Instead, the land department adapted land reform policy to better suit this profitable industry, playing catch-up to strong, centralized institutional veto players in the fruit sector. Yet while these reforms allowed for greater land transfers, they introduced new problems for land reform beneficiaries.

Until the Cows Come Home: Patchwork Land Reform in The Ranching Sector

While often held up as the sector that has redistributed the most land, the ranching sector in South Africa has actually redistributed land quite unevenly. In some provinces, landholders in the sector have redistributed around 30% of their land, while in others they have redistributed under 5%. I argue that this patchwork land reform occurs because of the institutional characteristics of the sector. While ranchers have the incentive to redistribute land to maintain biosecurity and preserve commercial red meat markets, the decentralized nature of the sector means that these incentives are only strongly felt in some areas. Therefore, while producers in some areas organize to transfer their land, others do not.

Reap What You Sow: Liberalization and Redistribution in South Africa's Grain Sectors

My final case study of land reform in South Africa focuses on the grain sector, where limited land reform took place. I argue that this is due to the fact that the deregulation of the once heavily supported grain commodity sector combined with the decentralized nature of grain farming to make landholders in the sector even less likely to sell their land. Due to vast changes and increasing pressures on marginal grain farmers, landholders had little incentive to sell to the land reform program and the sector itself had little capacity to push landholders to sell.